In baseball, the ultimate player (leaving out the pitchers) has outstanding skills in five areas – running, throwing, fielding, hitting for average and hitting for power. A “five tool” player possesses all five skills. Few players earn that label. Willie Mays and Barry Bonds are examples of players in this category. They were special because of their versatility and ability to affect a game in so many ways.

In baseball, the ultimate player (leaving out the pitchers) has outstanding skills in five areas – running, throwing, fielding, hitting for average and hitting for power. A “five tool” player possesses all five skills. Few players earn that label. Willie Mays and Barry Bonds are examples of players in this category. They were special because of their versatility and ability to affect a game in so many ways.

What about the “ultimate player” in Competitive Intelligence?

I submit that there are three fundamental categories of skills for competitive intelligence.

A “three tool” competitive intelligence professional will be competent all of these areas. When that is true, their value to their organization or clients is great. Admittedly, each category covers a multitude of skills. Moreover, mastering even one set of skills will make you valuable to someone. However, being proficient at all three makes you and your services standout.

Here are my three skill areas, or categories.

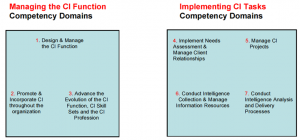

I. Table stakes. These are the basic skills needed by anyone conducting  competitive intelligence. Grouped in this category are analytical techniques, modeling approaches, data collection and interpretation, presentation delivery, project management and more. A useful list of skills and knowledge is contained at John Prescott’s Competitive Intelligence Book of Knowledge. Here is a diagram from his PDF file.

competitive intelligence. Grouped in this category are analytical techniques, modeling approaches, data collection and interpretation, presentation delivery, project management and more. A useful list of skills and knowledge is contained at John Prescott’s Competitive Intelligence Book of Knowledge. Here is a diagram from his PDF file.

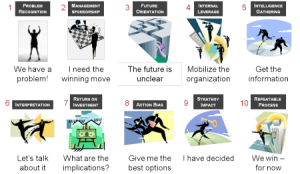

I have a similar taxonomy that I have described in 10 steps for competitive intelligence. The diagnostic questions for each step are listed in this file. Neither framework is sacrosanct. Their importance is that they attempt to describe completely fundamental tasks and skills.

Acknowledging that skills are critical, this category, in my opinion, gets a disproportionate amount of attention from Competitive Intelligence professionals. Although it makes sense to start with these skills, the inordinate preoccupation with them causes us to starve our other needed learning. Would it be better to become simply proficient and then move on?

II. Change management. Many times competitive intelligence professionals consider an analysis, well presented to be their services end point. That is, once the information is interpreted and given to senior management, the competitive intelligence task is over. No doubt that some organizations prefer and enforce this boundary. However, for competitive intelligence professionals, separating meaningful change from the analysis responsibility is a recipe for irrelevance. Why does an organization need great competitive information if it is disconnected from debate and devoid of influence in strategy discussions? The short answer is, “they don’t.”

The more powerful and compelling view of competitive intelligence is one that is recognizably useful in strategy discussions. The usefulness metric is a function of potential improvements to strategy. By definition, improvements imply change and change affects constituencies in the company. This involves people that are often found in prominent positions and have well developed opinions and biases. Therefore, the common challenge is to change the minds of powerful, well-placed people. The (usual) lack of positional authority for competitive intelligence people compounds the challenge. So, what skills are needed to persuade others to change? Here is a short list.

- Political awareness – There are decision-making rules (formal and informal) that are followed in any organization. Deciphering the informal ones is especially important because they affect how people behave. Mapping influential relationships often illuminate what otherwise seems opaque. This (and more) all matters greatly for accomplishing changes.

- Marketing – Every competitive intelligence professional needs to be good at telling stories. This is different from “presenting data” because stories are meant to convey more than information. Good stories are memorable, make an emotion connection for the listener and convey truth. Yes, they also transmit information but information transfer alone is a modest, unsatisfactory goal.

- Alliance management – Pity the competitive intelligence person that works by him or herself. Yet, many slave away doing web searches, monitoring Twitter and constructing PowerPoint slides in their office hoping to produce something of value. It may be possible to do so but it is unlikely. It is far more powerful to work with and through networks of people (inside and outside the company). The amplifying effect adds credibility. Building, nurturing and harvesting information from networks is critical.

- Change artistry – It is fine to spot the need for strategic change. Someone skilled at competitive intelligence may identify multiple strategy modifications. Which ones should be advocated? What is the most propitious timing for change? Who is emotionally, intellectually and spiritually ready to risk supporting the change? A change artist learns to plan actions in context of answers to those questions.

III. The Customer’s Mindset – My definition of competitive intelligence involves helping strategy leaders make better decisions. The strategy leaders are my customers. (See my series on Competitive Intelligence Notes.) Certainly, there can be many different strategy roles in an organization at different levels. No matter which role is served, their issues, problem solving tools, priorities and ways of thinking are critically important. Without that understanding, the distinct strategy dialect that practitioners and senior leaders use may be confusing to outsiders. “Non-strategy speakers” will find communication difficult and positive results consistently illusive. It is quite possible to learn how to speak the dialect if one invests to learn what the strategy leaders already know.

Many competitive intelligence people stumble with these skills especially when they intentionally of inadvertently position themselves separately from their customers. Of course, a competitive intelligence person cannot unilaterally promote himself or herself to senior management. What they can control, however, is their own education.

That is why the third tool for a complete competitive intelligence professional is proficiency in their customer’s mindset. Often this means that the missing education concerns strategy models, formulation, trends, techniques and more. If the customer is in a different role, then the list of training should mirror whatever they do most.

The value of getting an education in the customer’s area is that a competitive intelligence professional can better translate from their knowledge domain to the customer’s. That is when communication becomes effectively and positive change becomes possible. Without the sensitivity for the customer’s viewpoint, the delivery of interpretations is a hit-and-miss proposition.

The three tools go together. The table stakes are expected competencies. The change management skills have more meaning with effective analysis. Finally, the customer’s mindset shapes the application of table stakes skills and change management possibilities.

Would it not be better to be a “three tool” competitive intelligence professional?

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Anthony Poncier and Tom Hawes, Ian Smith. Ian Smith said: The “Three Tool” Competitive Intelligence Professional – http://tinyurl.com/yfmbq8y – great read for newbies […]

[…] “Three Tool” Competitive Intelligence Professional Check out The “Three Tool” Competitive Intelligence Professional from Strategically […]

I’d be interested to see a test of marketing and business planning professionals that actually employ the tactics and skillsets listed above.

I think you’ve done an excellent job in describing how competitive and market intelligence should be implemented.

I believe the core issue isn’t the potential value of the data but the capacity of the individuals doing the interpretation. Even with the easy to use tools today there is still a certain amount of market and data understanding that must be a part of any decision making process.

David,

In my experience, there are some (but not many) professionals of all types that consistently demonstrate these three skills. Most of their emphasis seems to be on domain skills; that is, the knowledge of their “native” discipline. This is not enough (IMHO) for someone that wants to affect the larger organization or to encourage meaningful change in an organization.

Tom