Early in my career, I supported the computers that ran a machine shop factory. The factory was a large, open room filled with machinery of every sort designed to form, cut and polish metal fixtures. I remember things about that factory. One memory is of the smell of machine oil. Another memory was of the cleanliness of the aisles between the production machines. The primary memory, however, was of the sound. When the factory was running (most of the time), there were all kinds of sounds. Drills, cutters, polishers and packaging machines were operating at the same time. Though it was possible to carry on a conversation in the factory, it was not the best place to hear or communicate important messages. Of course, overhearing conversations was just about impossible.

Early in my career, I supported the computers that ran a machine shop factory. The factory was a large, open room filled with machinery of every sort designed to form, cut and polish metal fixtures. I remember things about that factory. One memory is of the smell of machine oil. Another memory was of the cleanliness of the aisles between the production machines. The primary memory, however, was of the sound. When the factory was running (most of the time), there were all kinds of sounds. Drills, cutters, polishers and packaging machines were operating at the same time. Though it was possible to carry on a conversation in the factory, it was not the best place to hear or communicate important messages. Of course, overhearing conversations was just about impossible.

There were ways to get around all of this noise.

- You could take advantage of the times that the factory shut down. That removed all of the background noise. Unfortunately (if your goal was talking instead of production), this happened very infrequently.

- If you knew exactly who to talk to, you could move close to them and speak loudly. If you were the listener, the right strategy was to focus on the speaker’s words while ignoring the barrage of other sounds.

- If you wanted to “overhear” something, then the only recourse was to become involved in the conversation. That, of course, depended on the acquiescence of the other participants. Thus, you were unlikely to hear much of value accidently.

Conversely, some approaches would only make the problem worse.

- You would not want a goal of hearing everything that was being said in the factory. That would simply complicate the problem of separating an important conversation from the background machine noise. Lack of focus was a sure way to hear nothing of value.

- You would never want to amplify the sounds in the factory. Though this might increase the volume of the speaker’s voice, it would also increase the sounds from the machinery.

- You would not want to encourage people to whisper. Obviously, this made it harder to hear since the level of noise would overwhelm the conversation

Both of these lists could go on and on. They illustrate the common problem that we have of separating the important from the unimportant. The difficulty arises because every important communication is surrounded by background (i.e., contextually unimportant) noise. The world (much like the factory) is full of noise. What we want to hear is typically competing with so much that is unimportant (or less important). Furthermore, sometimes we want to “overhear” or discern things not originally meant for us. The background noise makes that task especially hard.

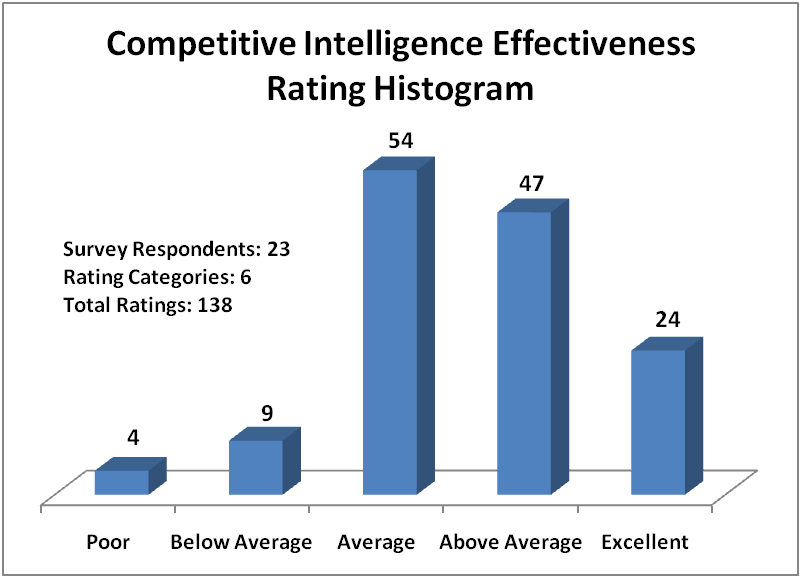

Thus, we get to the fundamental task in competitive intelligence. That is, targeting the signals that we desire to hear, decreasing the “volume” of the background noise and, finally, interpreting the important signals correctly.

Read the rest of this entry